Black Minstrelsy

Minstrelsy is a distinctly early, indigenous American form of pop culture. Its evolution can be traced to two entertainment sources in early America--white actors who impersonated black men between circus acts and black musicians who strummed a banjo and sang in the streets of a city. Black minstrelsy proper covered three different eras, and these phases are delineated as Antebellum era (1830-1861); the Reconstruction era (1861-1870); and the Jim Crow era (1870-1900) (Takacs). Each era embodied its own philosophy about race and race relations.

One topic, above all others at which minstrelsy considered itself an authority, was race. From its get-go, minstrelsy enforced the racial ideology that whites were superior and, conversely, blacks were inferior. White men dressed in gaudy clothes and wearing stylized blackface makeup danced, sang, and performed routines in exaggerated and stereotypical imitation of African Americans. Roediger concluded that this form of entertainment contributed to popular whiteness “across lines of ethnicity, religion, and skill” (127). These men, in their blackface persona, gained respectability in their rowdiness as well as creating an avenue for safe rebellion. Women and blacks bore the brunt of jokes during these minstrel shows, as both classes needed to be kept in their second-class places, and the hierarchy demanded that the white male occupy the first place. Political satire and bawdy jokes were staples of the minstrel stage, with women and the suffrage movement lining up for a share of ridicule. One such song went like this:

"When woman’s rights is stirred a bit,

de first reform she bitches on,

is how she can wid least delay,

just draw a pair ob britches on" (Strausbaugh 115).

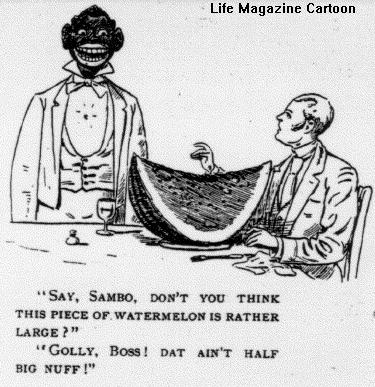

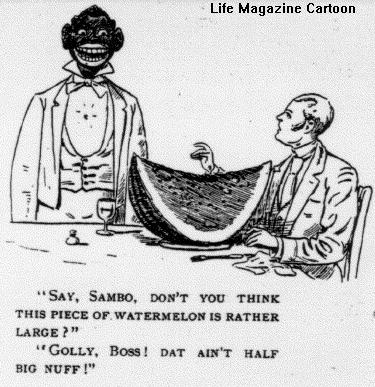

By donning the blackface mask, whites were saying this cultural and physical disguise emphasized their whiteness and whiteness really mattered. As the performers delivered their snappy jokes, they proclaimed they were ‘like widows’ in that they wore black but only temporarily (Roediger 117). Not only did blackface impersonators portray the black American’s physical appearance as being inferior, but attack what to them represented the black American’s culture. They gave them a superstitious nature, a biological tendency to be lazy, a compulsive lover of pleasure, dancing, and food; in particular, watermelons, and an abnormal belief in animal fables. Nothing could make a white audience feel more superior than when watching and laughing at the sight of a black-faced performer sing, dance, and eat watermelon at the same time. This type of childish behavior was certainly no threat to white societal dominance (Lee 2).

Life Magazine cartoon

Minstrel shows typically followed a format with standard characters from every opening scene. There was an interlocutor who appeared in burnt-cork makeup, but he did not speak in the exaggerated Negro dialect. The interlocutor was the cue-giver and mouthpiece, and he directed jokes to the two end men--Mr. Tambo (tambourine player) and Mr. Bones (bone castanets player). Class character corresponded to the minstrel line of performers. As a rule, the interlocutor perfomed with florid speech and in proper dress, representing the upper class while, simultaneously, ridiculing the ostentatious behavior of that upper class. The end men, by their dress and vernacular, were the "plantation nigger" or "Broadway dandy," often one of each (Saxton 122). A fiddle player was also standard fare, and when the music was played, it resembled a syncopated rhythm. Curry concludes that the musical sound and rhythm also imitated the call-and-response, African-American elements of song, much as they might have ‘hollered’ while working in the cotton fields (1). After the Minstrel Line and intermission came the middle portion of the entertainment, the Olio. This part might include songs and variety pieces with the last act often performed by one of the end men. This Olio format would eventually evolve into a newer form of entertainment and variety theatre called vaudeville. The third act, after the Olio, was usually a one-act, musical spoof of a popular topic of the day. One could expect to see "Jim Crow" depicted by T. D. Rice in this third act is where the raggedy buffoon was just waiting to be contemptuously derided.

Cullen, in Popular Culture in American History, provides this exchange between Mr. Bones and Interlocutor to demonstrate that dialogues and songs performed in minstrel theatre acted as surrogate language for social and cultural commentary and ethnic satirity:

"Mr. Bones: Mr. Interlocutor, Sir!

Interlocutor: Yes, Mr. Bones?

Mr. Bones: Mr. Interlocutor, sir. Does us black folks go to hebbin? Does we go through dem

golden gates?

Interlocutor: Mr. Bones, you know the golden gates is for white folks.

Mr. Bones: Well who's gonna be dere to open dem gates for you white folks?" (75-76)

Strausbaugh says that early minstrelsy was a "mess of entertainment and politics, love and hate, attraction and repulsion, class and race consciousness, sincere imitation, and cruel mockery" (92). In about 1832, Rice as Jim Crow could be heard stumping for Andrew Jackson:

"But Jackson he's de President,

As ebry body knows;

He always goes de hole Hog,

An puts on de we-toes (vetoes)

Old hick'ry, never mind de boys,

But hold up your head;

For people never turn to clay

'Till arter dey be dead" (92-93)

As with the above Bones and Interlocutor dialogue which implied that white folks were too lazy to open the heavenly golden gates for entry, the subtlety in this verse implies that "clay" was not the man to vote for--Henry Clay was Jackson's rival and a Whig to boot. Ironically, Jim Crow could not vote for Jackson nor Clay. Had he been able to cast his vote, would he have voted for Jackson who was a Southerner and a slave owner? (Strausbaugh 93)

Songs popularized on the minstrel stage are still in evidence. “Carry Me Back to Old Virginny” and “Oh! Dem Golden Slippers” were written by James A. Bland, a black songwriter. The former song was the state song of Virginia, with such lines as “There’s where the old darkey’s heart am long’d to go, / There’s where I labored so hard for old massa.” The song had been amended to dilute its blackface legacy, but was dropped as the official song by Virginia in 1997. Stephen Foster was born in Pittsburg, but wrote minstrel music that most folks can sing even today: “Oh! Susannah,” “Camptown Races,” “My Old Kentucky Home,” “Old Black Joe,” to name a few (Strausbaugh 119.) In a documentary on the life of Stephen Foster that aired on PBS, questions were asked of panel members that included Eric Lott who is author of a 1993 book on blackface minstrelsy and the American working class. When asked his opinion regarding whether blackface minstrelsy was only about caricaturing blacks, he agreed that it is a stage form that depends on caricature, but it was a desire for white actors to inhabit the bodies of black people, to act like them and impersonate them. What was happening is that the desire was present to take racial ridicule to the stage and to make fun. At the same time, the white actors were indulging in sport at the expense of black people and making a lot of money at the same time. Lott further concluded that during this stage performance, the white actor had a cross-racial interest in exactly what it feels like to be black (qtd. in PBS 1).

What is billed as the first talking picture in 1927 featured Al Jolson as The Jazz Singer in blackface. He is legendary as he's remembered on bended knee singing to his mammy. Historian Herbert Goldman said Jolson was not a racist; he was a minority (a Russian-born Jew), and was known to befriend black performers at a time when it was not kosher to do so (qtd. in Kenrick 4). Jolson's explanation was that blackface gave him the emotional freedom needed to take risks as a performer. Whatever his intentions, Goldman concluded that the sight of Jolson in burnt cork singing Mammy is a stark reminder of the racial and cultural mindset that minstrelsy embodied, and it is dismissed as an embarrassment today (qtd. in Kenrick 4).

Legacies of the minstrel stage remain in evidence in pop culture today. Children who grew up in the 1950’s and 1960’s share memories of the Uncle Remus' trickster stories. Joel Chandler Harris wrote these stories about Uncle Remus and tales of Brer Rabbit, Brer Fox, Brer Bear, and Tar Baby in a dialetical 'Negro' dialogue. It was a bright moment when Brer Rabbit used his cunning to outsmart Brer Fox or Brer Bear. For children of a more youthful culture, Brer Rabbit's image is recognizable in the 20th Century wise-cracking Bugs Bunny (Strausbaugh 169). Strausbaugh further concludes that kind-hearted Uncle Remus strolled into a context that emerged as the Reconstruction period was ending and the harsh backlash of the Jim Crow era was getting started. White readers, he said, Southern and Northern, would see Uncle Remus as a beloved archetype of the antebellum plantation, the happy darky, and that same smiling blackface who performed on the minstrel stages (170). Harris sold his stories to Walt Disney who made a full-length feature film called "Song of the South" in 1946. The film is not considered politically correct when measured by today's yardstick.

Other legacies of the minstrel theatre and particularly the Jim Crow name was given to segregation laws enacted in the south. These laws were discriminatory ones specifically aimed at African Americans and dealt with public school attendance and use of public facilities such as buses, theaters, hotels, etc. Some states forbade marriage between the two races.

Shauneille Perry is a professor of theatre and black studies at new York’s Lehman College, and she wrote in American Theatre that the black mask has “hypnotized our society since it began, seducing blacks and whites in different and interrelated ways” (2). She goes on to say that blacks are not given license to be themselves in today’s culture; that Spike Lee got it right in Bamboozled as did Marion Riggs in his 1987 documentary, Ethnic Notions. The burning cross, lynch rope, ball and chain, and whip are still very much alive in contemporary culture (2).

The link to Ethnic Notions will further inform when navigating to Racial Formation in Modern American Cartoons with sub-headings of World War II, Bugs Bunny, and the Censored Eleven. Riggs' Ethnic Notions was viewed and critiqued in American Studies class, and Bamboozled, in Lee's words, is "an exploration of history of racism" and intends to be a controversial depiction of how people of color have been misrepresented since the birth of film (2). Bamboozled was filmed in 2000; it was about a frustrated African-American TV writer who was unsuccessful in getting approval and backing for a 'Cosby-esque' show, so he proposed a blackface minstrel show in protest; to his dismay, it became a hit. At the Bamboozled website, a brief history of blackface minstrels and African Americans on television is offered for further reading: http://www.bamboozledmovie.com/minstrelshow/briefhistory.html.

Blackface minstrelsy enjoyed a prominence abroad, and it had a particularly receptive audience in Scotland. It seems fitting to borrow thoughts from a reviewer in The Glasgow Theatrical Review in 1847, when he summed up the dichotomous nature of blackface: "Sir Walter Scott [Saloon] rejoices in the possession of a corps of Ethiopians of the true Dan Tucker stamp. Able, animated and original, throwing energy into their effusions, and darking headlong into the wild humour, and witticism of that race, who, deprived of some portion of liberty, are by that process released from the cases, the anxieties, and the everlasting mental calculations which makes his whiter brethren--wiser it may be--but also sadder men" (Rosset 422).

Further Reading

Lhamon, W. T., Jr. Raising Cain: Blackface Performance from Jim Crow to Hip Hop. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1998.

Lott, Eric. Love and Theft: Blackface Minstrelsy and the American Working Class. New York: Oxford University Press, 1993.

Works Cited

Curry, Andrew. “Men in blackface.” U. S. News & World Report (July 8, 2002): 24. Expanded Academic ASAP. Gale. Oklahoma State University of Tulsa. 8 Nov. 2007 <http://find.galegroup.com/itx/start.do?prodId=EAIM>.

"Interview with Spike Lee, writer, director,co-producer of Bamboozled." PopMatters. Month/Day Unavailable, 2000. 26 Nov. 2007 <http://www.popmatters.com/film/interviews/lee-spike.shtml>.

"Jazz Singer, The": Jolson." Online Photograph. Encyclopedia Brittanica Online.

<http://www.britannica.com/eb/art-12147>.

Jones, Jacqueline. "Blackwell Readers in American Social and Cultural History." Ed Jim Cullen. Popular Culture in American History. Brandeis University: Blackwell, 2001. 75-76.

Kenrick, John. "A History of the Musical Minstrel Shows: Part II." Musicals101.com. Home page. 01 Dec. 2007

<http://www.musicals101.com/minstrelb.htm>.

Lee, Jason H. "Minstrelsy and the Construction of Race in America." African American Sheet Music. Brown University. 12 Oct. 2007 http://dl.lib.brown.edu/sheetmusic/afam/minstrelsy.html>.

[This source acknowledged with a potential limitation on reliability. Mr. Lee wrote this paper in partial fulfullment of an academic requirement for his studies in American Popular Culture at Brown in 2004. His professor signed off on the paper.]

Perry, Shauneille. "Blacker Than You, Brother Man." American Theatre 21.2 (2004) 08 Nov 2007 <http://find.galegroup.com/itx/printdoc.do?contentSet=IAC-Documents&docType=I...>

Roediger, David R. The Wages of Whiteness. London: Verso, 1991: 115-131.

Rosset, Nathalie. "The Birth of the 'African Glen': Blackface Minstrelsy Between Presentation and Representation." Rethinking History 9.4 (2005): 415-428. Vol. 9. Oxfordshire: Routledge 2005. 422.

Saxton, Alexander. "Blackface Minstrelsy and Jacksonian Ideology." Locating American Studies, The Evolution of a Discipline. Ed. Lucy Maddox. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins, 1999. 122.

"Stephen Foster." American Experience. PBS. 01 Dec. 2007 <http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/foster/sfeature/sf_minstrelsy_6.html>.

Strausbaugh, John. Black Like YOU. New York: Penguin Group, 2006.

Takacs, Stacy. Lecture. Theories and Methods of American Studies. Tulsa. 16 Oct. 2007.