To most people, comic books represent a genre of popular culture that screams immaturity and adolescence. Costumed vigilantes running around—or sometimes flying around—fighting costumed villains, who seem to always get busted, get thrown in jail only to make another appearance on the streets of the city later on. Funny enough, “most people” are correct. This monotonous cycle of vigilante, cowboy antics are perfect for attracting young males between the ages of ten to twenty-one (Pustz xii). To many, comic books are nothing more than a harmless pop culture avenue to cull the masses of young boys needing a medium through which to pacify their newly formed primitive needs of violence and sex. To some, they can be an entertaining and therapeutic method of breaking life harsh realities to such a young and spoiled American youth. To others, comic books can be a powerful tool for reaching this shifty and ever fickle demographic who are soon to be Americas future leaders.

As Bradford W. Wright, author of Comic Book Nation, writes: “comic bookshave helped to frame a worldview and define a sense of self for the generations who have grown up with them. [Also,] they have played a crucial explanatory, therapeutic, and commercial function in young lives” (Wright xii). Comic books have played a crucial role in the lives of many young men and some women too. Comic books, like most media forms, tend to inadvertently educate their readers as well as entertain them. It might shock a few parents for them to learn their young boy or girl could be reading a comic book that’s subject matter deals with the hardships of their parent’s lives. “In an interview on National Public Radio… Captain America, Axel Alonso [said]: ‘[W]hat I’d say is our responsibility as writers, artists, editors and creators is to create narratives that have a point [and] perhaps educate on some level’” (Dittmer 627). This has the potential of making comic books a geopolitical machine that brings the world’s political and social problems down to a level young children and adolescents can understand. But, could it all be that positive? Could comic books also be used to promote social ideals as well inform the public?

The Kryptonian Progressive Reformer

Comic Book’s first real super powered, superhero was none other than Superman. Originally created by for newspaper comic strips, Superman eventually found his way to an industry and helped turn it into what it is today (Wright 9). Superman’s archetype is one that all Americans have seen before, the American Cowboy. Like the Cowboy, Superman “resolve[d] tensions between the wilderness and civilization while embodying the best virtues of both environments himself” (Wright 10). Unfortunately for Superman when he finally came along, the west had been conquered. There were no half-naked savages running around for Superman to stop. Superman was conceived during the Postindustrial Era of the 1930 (Wright 9). During this time, the common man’s enemies were seen to be a little better clothed and a little whiter.

Many of Superman’s tales narrate a common story between corporate greed and the public welfare (Wright 12). Bradford Wright illustrates a few great examples of this starting with Action Comics #3:

One early story opens with Superman rescuing a miner trapped in a cave-in. The injured miner later tells reporter Clark Kent [(Superman’s alternate identity)] that the mine tragedy could have been avoided if the owner and foreman had heeded warnings about unsafe working conditions... [After interviewing the miner owner,] Superman traps the owner in a cave-in and lets him experience the misery that the miners had to endure (Wright 11).

This is just one of the many examples of Superman using his vastly superior and otherworldly powers not to save Earth of a crashing meteor or some equally powerful villain. Superman’s adventures continue and range from plots to stopping people who would plunge America into another Great Depression to foiling plots by crooked stockbrokers selling worthless stocks (Wright 12). Superman, instead, uses his fantastic abilities to defend the common American from the greed of others both foreign and domestic.

For the people reading Superman at the time, Superman signified a costumed Franklin Delano Roosevelt. “The New Deal… was an effort to redirect people to look to a powerful force—the federal government—to serve as their benefactor, their protector against greedy and corrupt local interests” (Time). Even though the government did not subsidize the writers of Superman, FDR surely benefitted from their work, which created a public who looked at Superman as a necessity toward getting a fair shake. If the young Americans were brought up to truly believe that in order to get through life, they needed a powerful individual to help them out, in the world of reality, whom would they look to?

Heroes go to War

The Great Depression saw the growth of the comic book genre explode. With books selling for 10 cents a piece and offering a medium of escape and pacification for the youth caused these cheap pieces entertainment took off. Copies of Action Comics (Superman’s home) were selling by the millions each week, but the readers of comics were about to be introduced to a conflict much more By the 1939, Germany had invaded Poland and the war in Europe had begun. America was stilling coming out of the Great Depression and isolationists believed that a war in Europe had no bearing on America.

Long before the United States government went to war against the tyranny of the Nazi’s, superheroes and comic books, as a whole, were fighting the fight for them. Stan Lee, creator of many of Marvel Comics most popular superheroes, said it simply: “We, just, could all see what a menace Hitler really was. It was more than what he was doing to the Jews, it was what he was doing to the whole world. He was gobbling up countries” (Time).

With corporate greed and the American worker being taken care of by FDR’s New Deal, comic books decided to shift their focus toward this new, global enemy. Superman was one of the first to decide to get into the action. In two short pages, Superman flies to Germany, picks up Hitler and his then partner Stalin, and flies them to The League of Nations for trail and punishment (Time). DC Comics—Superman’s publisher—was soon joined by Marvel Comics in this war on Hitler with the birth of their most iconic superhero to date: Captain America.

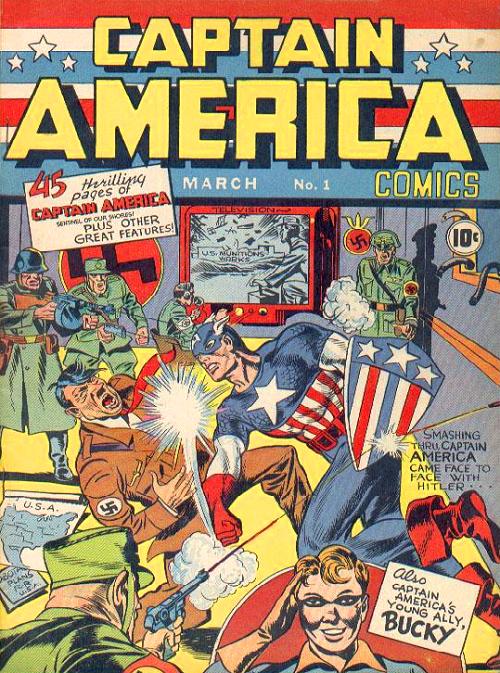

In his debut comic, Captain America is shown on the cover clothed in the American flag, delivering a smashing right hook to Hitler. Part of the “super soldier program” created by FDR, Captain America, along with his sidekick Bucky, “bravely faced Nazis, Japanese, and other threats to America during the Big War” (Rhoades 37). But, Captain America stood for more than a heroic American figure that was sure to single handedly end the war:

“In contrast to the complex and controversial issues surrounding the Great Depression, the outbreak of World War II united Americans in opposition to a common enemy,” writes historian William W. Savage, Jr. “Comic book publishers seized upon the national mood and created heroes, such as Captain America, that reflected the newfound patriotism" (Rhoades 37).

It probably doesn’t need to be asked if such use of comic books actually helped out the government effort to wage the war. During this time, Roosevelt founded government agencies such as the Office of Facts and Figures and the Office of War Information (OWI). It was during this time that “[t]he OWI urged entertainment producers to voluntarily conform to administration guidelines and ask themselves of all their products, ‘Will this help the war?’”(Wright 34). Considering FDR’s direct involvement in the effort, one would hope he might get the results he was looking for.

Adolescent Involvement in Wartime America

The war in Europe was an interesting and plentiful topic when it came to creating plotlines and stories for comic circulation. But the primary audience for these stories where children: a demographic that was the least affected by the war, directly as it were. Kids were not going to be fighting or managing the war, nor were they going to be in the factories helping create ammunition and vehicles for the war effort. But, that didn’t stop comic book developers from pursuing their help in the war effort. One of the many wartime efforts President FDR put into effect during World War II was a conservation act that promoted recycling for war materials. In order to help out, “Superman urged readers to give to the American Red Cross. Batman and Robin asked boys and girls to ‘keep the American eagle flying’ by purchasing war bonds and stamps. Captain America and his sidekick Bucky showed readers how to collect paper and scrap metal” (Wright 34). “Wonderwoman [also] gave down to earth advice to kids… urging them to collect old paper and scrap metal” (Time). Comic book superheroes played a crucial role in involving children in wartime aid. But, after the war, superheroes saw their usefulness decline.

Comic books had reached their peak in the early 1950’s. With the federal mandate of paper rationing lifted at the end of the war, comic books makers were able to print and sell as much as they wanted. Unfortunately, this didn’t help sales of comic books featuring the heroes that meant so much to the war effort. Readers became interested in genres featuring childlike animal characters, teen comedies, westerns, and mysteries (Time). The lack of any enemy or national/global crisis saw the usefulness of superheroes diminish:

A recovered economy, government assistance programs like the G.I. Bill, and the mass construction of affordable suburban homes made a middle-class lifestyle possible for millions. By appearances at least, the helpless and oppressed who cried out for Superman in 1938 now lived comfortably and contentedly in the suburbs. Superheroes animated by the crusading spirit of the New Deal and World War II seemed directionless and even irrelevant now that those victories had been won (Wright 59).

Superheroes saw themselves making large transitions in their persona and character. Batman carried a badge; Superman became the ultimate symbol of patriotism and lawfulness with a new slogan saying that he “fights a never ending battle for truth and justice, and the American way” (Time). But, as comic books began to lose their popularity and their importance to the social scene, the superheroes would soon find themselves fighting the most powerful force the world had known at the time: The United States Government.

1950's Attempt to Censure Comics

During the mid-1950’s, a man named Fredric Wertham started a crusade against comic books. After being senior psychiatrist at Bellevue and being appointed director of the Psychiatric Clinic at Queens Hospital Center, Wertham opened a low cost psychiatric clinic in Harlem (Wright 93). After treating juvenile offenders in New York, he found that many of his patients read comic books. After making the connection, Wertham wrote about this connect in his book “Seduction of the Innocent.” Wertham even went so far as to attack Superman naming a condition after him called “The Superman Complex” (Time). He defined the complex as, “fantasies of sadistic joy in seeing other people punished over and over again while you, yourself, remain immune” (Time). Batman and Robin were attacked as, “like a wiz-dream of two homosexuals living together” while “Wonderwoman was the exact opposite of what girls were supposed to be “(Time). The book’s popularity led to hearings on Capital Hill.

If this sort of witch hunt were to happen in the twenty-first century, accusations of encroachment on freedom of speech and other first amendment arguments would be made. Public outcry would be created to put the government back in its proper place, but comic books publishers didn’t have the lack of trust in government the media and American people carry today. With the escape from the Great Depression and victory in World War II, American’s had trust and sometime blind-faith in their elected officials. Comic book publishers followed this public sentiment by self-censuring themselves by creating the Comics Code Authority.

This organization, created and funded by comic book publishers, would review every comic before publishing and offer a seal of approval (Time). The CCA wrote up a set of guidelines that spelled out the comic book publisher’s willingness to fly right and play by the rules:

Superman worked closer than ever with lawful authorities; Batman and Robin spent more time with girls; And Wonderwoman hung out more with Steve, but superhero relationships stayed at the level of grade school crushes… The code also enforced rigid rules of conformity. About authority, it said “Policeman, Judges, and Government Officials and respected institutions shall never be presented in such a way as to create disrespect for established authority” (Time).

These strict self-enforced guidelines had done the trick in removing government pressure from their industry, but the sales of comic during that time plummeted and it would be a long time before they would recover.

Conclusion

So, do comic books try to educate children in about certain political and social topics? Or do the publisher’s access to children give them an opening into using comics as a pulpit to preacher to the youth culture? It is important to understand that comic books, like every other media in America, are a business. The one—and sometimes the only—thing businesses tend to care about is the bottom line, money! And like any good business, it will do what it needs to do in order to make that money.

Media typically does not try to shape public opinion, it tries to immolate it. Would comic books have attracted so many readers during the Great Depression if comic books reflected a pro-corporation mentality? Would comic book’s popularity peak during World War II if characters like Superman and Captain America had been isolationists that spoke out against the war rather than for it? Media tends to reflect popular opinions and ideals because it would reach a larger audience and would sell more issues. It would seem correct to be tough on comic book’s lack of objectivity when it clearly helped out efforts of President LBJ and the government as a whole, but a closer look at other media forms shows a consistent pattern that mimics the messages of comic books as well. While we might want to believe that the American media, as a whole, is unbiased when it comes to political issues. Well, they aren’t. And it is not because they can’t do it, it is because nonpartisanship doesn’t sell. Everyone has an opinion and any media form that reflects that opinion is going to receive the dollars of those they appeal to. It is nothing personal, it is just business.

Bibliography

Dittmer, Jason. "Captain America's Empire: Reflections on Identity, Popular Culture, and Post-9/11 Geopolitics." Annals of the Association of American Geographers 95 (2005): 626-43.

“Time Machine – Comic Book Superheroes Unmasked.” History Channel. 25 Nov. 2005.

Pustz, Matthew J. Comic Book of Culture :Fanboys and True Believers. New York: University P of Mississippi, 1999.

Rhoades, Shirrel. A Complete History of American Comic Books. Grand Rapids: Peter Lang, Incorporated, 2008.

Wright, Bradford W. Comic Book Nation : The Transformation of Youth Culture in America. New York: Johns Hopkins UP, 2001.

Researched, composed, and written by Robert Danklefsen